Arthrocentesis

INDICATIONS

- Arthrocentesis is used to establish the cause of an acute monoarthritis or polyarthritis.

- Nongonococcal bacterial arthritis is a “do-not-miss” diagnosis, since a delay in identification and treatment may lead to clinically significant joint destruction and even death.

- Other infectious causes include disseminated gonococcal infections, tuberculosis, fungal infections, and Lyme disease.

- Crystal arthropathies (gout and pseudogout), rheumatic disorders, osteoarthritis, trauma, and hemarthrosis may also lead to acute joint effusions.

- Arthrocentesis is also used as a therapeutic procedure, to drain large effusions or hemarthroses, and to instill corticosteroids or local anesthetic.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

- Cellulitis overlying the site of needle entry.

- Suspected bacteremia is a relative contraindication to arthrocentesis; if septic arthritis is suspected, however, the procedure should be performed.

- The safety of arthrocentesis has not been established for patients with coagulopathy or patients who are receiving anticoagulant medications, and the use of reversal agents or products (e.g., fresh-frozen plasma or platelet concentrates) should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

COMPLICATIONS

Arthrocentesis is a relatively benign procedure, and if properly performed, complications are rare. Potential complications include iatrogenic infection, localized trauma, pain, and reaccumulation of the effusion

PREPARATION

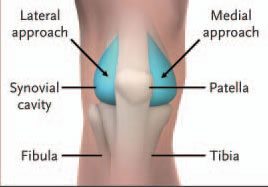

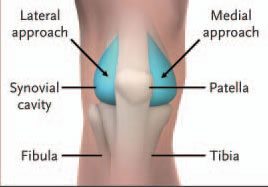

- The knee may be tapped from either the medial or the lateral side.

- The patient’s knee should be extended or flexed at an angle of 15 to 20 degrees.

- The needle will enter the skin 1 cm medial (or lateral) to the superior third of the patella and is directed toward the intracondylar notch.

JOINT ASPIRATION

- Explain the procedure to the patient, obtain written informed consent, and then gather the equipment you will need.

- Position the patient supine on a stretcher, with his or her knee extended or slightly flexed.

- Identify the landmarks and demarcate the entry site with a skin-marking pen, or use another appropriate method.

- Prepare the skin with a cleansing agent such as povidone–iodine or chlorhexidine. You may place a sterile drape around the site.

- Begin to anesthetize the region by placing a wheal of lidocaine in the epidermis, using a small (25-gauge) needle, and then anesthetize the deeper tissues in the anticipated trajectory of the arthrocentesis needle. Intermittently pull back on the plunger during the injection of the anesthetic to exclude intravascular placement.

- Using an 18-gauge needle and large syringe, direct the needle behind the patella and toward the intracondylar notch. Resist the temptation to “walk” the needle along the inferior surface of the patella, since this practice may damage the delicate articular cartilage.

- Constantly pull back on the plunger while you advance the needle; you will know when the needle enters the synovial cavity, because fluid will enter the syringe.

- You should remove as much fluid as possible. “Milking” the effusion, by gently compressing the suprapatellar region with the opposite hand, may aid in this endeavor. In cases of large effusions, you may need a second syringe to complete the aspiration.

- Once the aspiration is completed, remove the needle, cleanse the skin, and apply a bandage. You may apply a woven elastic bandage or knee immobilizer to reduce post procedural swelling and discomfort.

TROUBLESHOOTING

Failure to aspirate synovial fluid results in a “dry tap.” Misdiagnosis of knee effusion, obesity, obstruction of the needle lumen by particulate matter or a plica, or hypertrophy of the synovium (owing to chronic inflammation) may all result in a dry tap. If the medial approach was used initially, a lateral approach should be attempted, since this may overcome difficulties presented by a medial plica or thick medial fat pad.

SYNOVIAL-FLUID ANALYSIS

Collected fluid should immediately be placed into appropriate containers and analyzed expediently. Check with the laboratory regarding specific submission procedures (e.g., the correct tubes and the volume of fluid required for each test). If only minute volumes of synovial fluid are obtained, discussions with laboratory personnel are indicated to prioritize testing. As little as one drop of fluid may be sufficient for crystal analysis, and 1 ml may suffice for a cell count and a differential count.

Gram’s Staining and Culture

Gram’s staining and culture of synovial fluid provide the most definitive evidence of septic arthritis. The sensitivity of these techniques is much higher for nongonococcal infections (50 to 75 percent for Gram’s staining and 75 to 95 percent for culture) than for disseminated gonococcal disease (less than 10 percent and 10 to 50 percent, respectively.) If gonococcus is suspected, cultures of the blood and of urethral, rectal, or oropharyngeal swabs should be considered. To minimize the risk of contamination, the synovial fluid is often submitted for testing in the syringe used for the arthrocentesis.

Cell Count and Differential Count

The cell count and differential count are used to differentiate between non inflammatory effusions (e.g., osteoarthritis and trauma) and inflammatory conditions (e.g., septic and crystal-induced arthritis). A cutoff of 2000 white cells per milliliter and 75 percent polymorphonuclear cells is generally used. It should be emphasized that

the cell count and differential count cannot reliably differentiate among various

inflammatory entities. For example, up to 33 percent of patients with septic arthritis

may have white-cell counts below 50,000 per milliliter, and patients with

acute gouty arthritis may have counts exceeding 100,000 per milliliter. Synovial

fluid is usually submitted for cell and differential counts in specimen tubes treated with EDTA.

Crystal Analysis

Evaluation of synovial fluid under a polarizing-light microscope may reveal the presence of monosodium urate crystals (seen in gout) or calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate crystals (seen in pseudogout). The sensitivity of crystal analysis is relatively high (80 to 95 percent for gout and 65 to 80 percent for pseudogout). It should be noted that the presence of crystals does not exclude the possibility of

septic arthritis, since the two conditions may coexist. Synovial fluid is usually submitted

for crystal analysis in a lithium heparin–treated specimen tube.

Other Tests

Although often ordered, biochemical assays such as for glucose, protein, and lactate

dehydrogenase have little discriminatory value and should not be included in

routine synovial-fluid analysis. Other tests, such as specific stains and cultures for

atypical infectious agents and cytologic evaluation for suspected malignant effusions,

may be indicated in certain situations.

n engl j med 354;19 www.nejm.org may 11, 2006